In recent years, the term “breathwork” has become a misunderstood fad – a term that’s been lumped in with new age-y concepts like chakras and horoscopes. Yikes!

Third eyes and Pisces season aside, REAL breathwork is imperative if you’re looking to feel and perform better. In the present article we’ll discuss the two main ways in which breathwork can positively influence your health.

The benefits of breathwork come by way of…

#1 – Changing your physiology through breathing.

#2 – Changing your biomechanics through breathing (perhaps more accurately described as “fixing” or “restoring” normal breathing mechanics).

Both breathing-related outcomes are important. Very important.

Changing physiology is important in the contexts of performance, recovery, and emotional control.

As an example, someone who’s feeling sluggish while training might hyperventilate to create a positive surge of catecholamines (energy-releasing stress hormones) to get them through a challenging workout.

Someone who needs to chill from a stressful situation, or recover from a hard training session might slow their breathing to elicit the body’s “rest and digest” response, as well as allow for better cellular respiration (blood cells off-loading oxygen to the tissues of the body that need it).

Changing biomechanics is important in the contexts of mobility and pain-free movement.

Being able to expand and compress the axial skeleton (the spinal column, skull, ribcage, and for the purposes of this conversation, the pelvis as well) in every which way is the foundation for any lasting improvements in mobility. For example, re-learning how to get a full breath in and out will improve your shoulder range of motion, but not the other way around. Re-learning how to get a full breath in and out will improve your hip range of motion, but not the other way around.

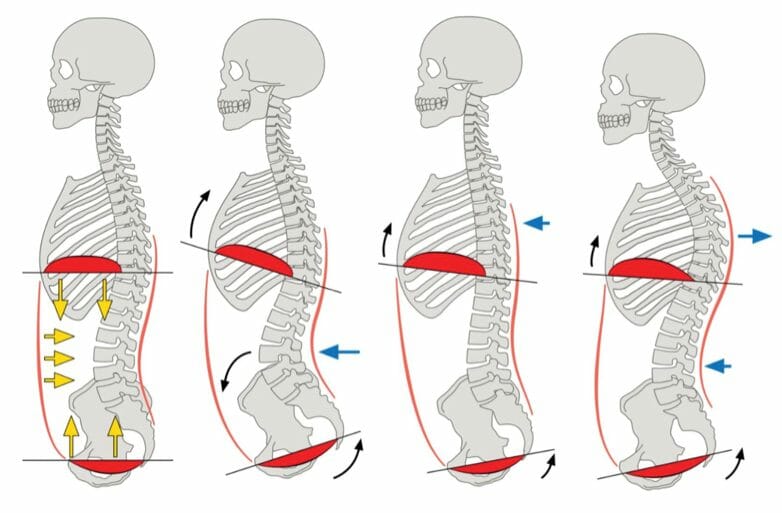

Establishing a good pelvis-ribcage relationship is key for efficient, pain-free movement. Some call this the “stack”. Others call it “canister position”. Forget the semantics, all you’re really doing is making sure the pelvis and ribcage are oriented in a way that’ll allow you to manage the pressures inside your torso appropriately for whatever movement it is that you’re trying to perform. You do this by restoring normal breathing mechanics.

Breathing to change physiology

Breathing to change physiology is the easy one. Easy to understand and easy to apply. All you really have to commit to memory is that…

#1 – Nasal breathing is better for staying calm. Mouth breathing is better for feeling stressed.

#2 – Slow breathing is better for staying calm. Fast breathing is better for feeling stressed.

#3 – The exhale is linked with parasympathetic activity, and the inhale is linked with sympathetic activity. In other words, focus on slower exhales to stay calm. Focus on fast, sharp inhales to elicit a stress response.

Pretty simple, right? The next time you’re feeling stressed, breathe slowly through your nose and make sure the exhale lasts longer than the inhale. Conversely, if you need a boost in energy, breathe quickly through your mouth.

Breathing to change biomechanics

Breathing to change biomechanics is a lot more complex. Luckily, I’m here to simplify the information so that you, my fellow human performance enthusiast, can take your health into your own hands… or lungs. First, let me describe the key concepts related to fixing your breathing mechanics.

#1 – Your breathing mechanics can be compromised due to injury (physical trauma), being locked in a startle response (stress and mental/emotional trauma), sedentary living (staying in the same postures/positions), and/or lack of movement variety.

#2 – Compromised breathing mechanics = losing the ability to compress and/or expand key regions of your axial skeleton which in turn puts undue strain on other structures of the body. For example, someone who’s lower back is unable to expand (via positioning, and a good quality inhale) might have a pelvis that’s tipped forward and knees that hurt because of the constant shearing they experience from pulling back on a skeleton that’s “falling” forwards. During unloaded movements (e.g. walking, running, jumping), having normal breathing mechanics allows your body to disperse force throughout ALL of its joints. Normal breathing mechanics = all ranges of motion are available at the pelvis, ribcage, skull, and spine = subconscious micro-movements can occur around the pelvis, ribcage, skull, and spine to evenly distribute strain across the entire body.

#3 – During loaded movements (e.g. deadlifting, overhead pressing), having normal breathing mechanics allows you to create a good “stack” of your ribcage over your pelvis, which sets the stage for you to create the intra-abdominal pressure necessary to turn your torso into a stable (hernia-free!) unit for safe and effective lifting.

Next, let me walk you through the step by step approach I use to help my clients restore their breathing mechanics to get out of pain and move better…

3 steps to restoring normal breathing mechanics

#1 – Learn to fully exhale so that your skeleton has no option but to orient the ribcage right over the pelvis. The FULL exhale is key because, emptying out your lungs = getting the pelvic floor and thoracic diaphragm to ascend together, whereby the skeleton has no option but to “stack” itself nicely.

#2 – Learn to create intra-abdominal pressure via an expansive 360-degree inhale strategy. Now that the positioning of your bones (i.e. the pelvis-ribcage “stack”) is correct, it’s time to learn how to create pressure inside your torso, to varying degrees. For example, when you’re walking, you might only have your torso 10% pressurized. When you’re squatting heavy, you might have your torso 100% pressurized. And by the way, this “pressurization” should be a subconscious process which is why I’ll usually prescribe the following drill for 5min+ to ingrain the breathing strategy so deeply that it becomes automatic.

#3 – Utilize tempo lifting with breathing to open up areas of the pelvis or ribcage that stay “stuck”, even after doing the exercises laid out in steps 1 and 2. For example, I might give this to you if you had trouble getting a full breath in and out of your pelvis. I might give this to you if you had trouble opening up the back of your ribcage. And I might give this to you if you had trouble opening up, or “gapping” the spaces in between your ribs.

To recap: Understanding how to breathe is one of the most important things you’ll ever learn if you’re in the pursuit of better health and performance. Breathing to change your physiology is pretty simple. Breathing to change your biomechanics is a lot more complex, but the juice (pain-free, efficient movement) is certainly worth the squeeze (laying on the floor to do a few easy breathing drills; see above).

I tried to simplify the biomechanics of breathing as much as possible, but if you need clarification on any of the topics we discussed today, or if the generalized advice I gave today was too broad and you need specific guidance to solve your unique problems, feel free to shoot me a message. I’d be honoured to play a part in your health and performance journey :).

Pat Koo

BKin, CSCS